There have been numerous accounts in scholarly manuscripts, in the popular press, in memoirs, biographies, and even in novels about many of the famous artists and writers who escaped Vichy France from Marseilles, including Hannah Arendt, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Leon Feuchtwanger, and Heinrich Mann with the help of two wonderfully resourceful rescuers: Hiram Bingham, IV, the Vice Consul, United States Consulate in Marseilles, 1939 – 1941, and Varian Fry, of the Emergency Rescue Committee, in the 1940s. Thanks to a brilliant and recent novel by Julie Orringer, The Flight Portfolio (2019); see: Julie Orringer) the risks that these courageous people took vividly come to life. Her empathetic view of Fry is interesting in that she characterizes him as a gay man whose strength in his personal life gave him the ability to maneuver an unusual public persona as well. There are countless other books: Varian Fry’s own words: Surrender On Demand (originally, 1945, with new afterword, 1997 that had been re-published by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) is a fascinating account of his role, as well as that of Bingham. See also, more recently the article: Alex Ross, The Haunted California Idyll of German Writers in Exile | The New Yorker March 2, 2020 (print on March 9th) who highlights the role of Vry, but sadly omits Bingham’s crucial role.

What may be less well known is that thousands of ordinary people also traveled first to Spain and then Portugal and then managed to make it to the United States. Interestingly, for some of the emigrants their final exit (or for some temporary sojourn) to the United States is the culmination of a plan that began years earlier and show that these emigrants were finally successful, in that they had been planning an escape from war-torn Europe for some time.

My grandfather is one example. (Note: while his legal name was Dr. Schlioma Gruenberg, he is sometimes referred to by a variant of his first name Solomon, Salomon, or even Schlema, while my mother had referred to him by his family nickname, Leoma. Since I had never met him, throughout this post I will use his last name, that is the slightly Americanized version of it: Grunberg, to show respect.). Grunberg had been planning to arrange a way for himself, his wife, and daughter, my mother, to leave the Continent temporarily, if necessary – despite enjoying their rewarding lives in Berlin and then in Paris – for 20 years. It was the culmination of an exit or perhaps contingency strategy that in some ways had begun when they left the newly created Soviet Union in 1920. While his plan was not clearly defined until many years later, it is clear that his various experiences provided him with the foresight to realize that while new living solutions to the existential crises of these years worked, they needed to be periodically updated, depending on how the situations evolved. Rather than desiring a direct exit from Continental Europe – as others had done – Grunberg saw himself as European and wanted to stay in parts of Europe as long as possible. And, should they need to leave, to return.

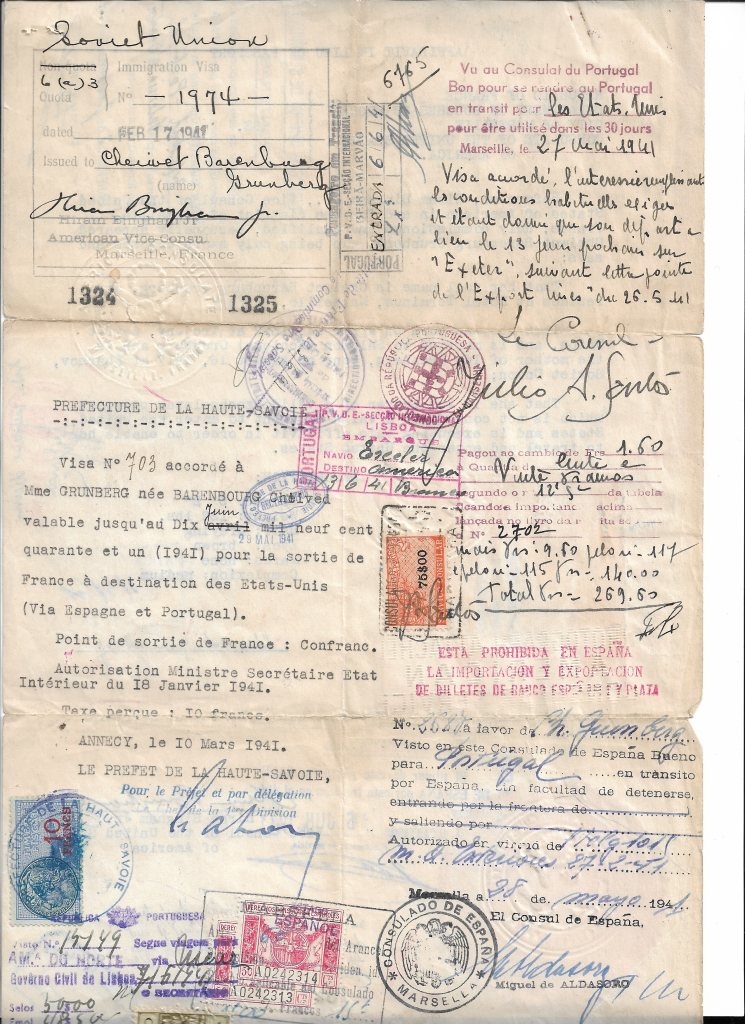

The following is a brief description of the ways in which he planned a successful escape from war-torn Europe and in the spring of 1941 finally joined his younger brother in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. As the record (see the attached affidavit in Appendix II for my grandmother) shows, they needed to be patient, as well as quietly resourceful. While my grandfather was able to acquire permission for himself, his wife, and his 24-year-old daughter to leave France – in lieu of a visa – on February 17, 1941 and travel to Spain and then Portugal and on to the United States, they only actually left Marseilles on May 27th.

My grandfather, Schlioma Grunberg (1882-1943) was born in Trojany, then Russia, now Ukraine: the eldest son in an upwardly mobile Jewish family, he was a resourceful and forward-thinking man. Grunberg was a medical doctor, an attorney, and an entrepreneur. Married in 1912 to my grandmother, Cheiwet Barenburg (1887-1983) the daughter of one of the wealthiest sugar planters, also Jewish, in the Sablino Province, Kherson, then Russia, now Ukraine.

My grandparents met in Odessa, where my grandfather had been studying law (after acquiring his medical degree in Vienna) and where my grandmother was studying chemistry (after having taken courses in Liege, Belgium) and after their marriage he worked as the corporation attorney for his father-in-law; they settled in Kharkov. He served as an officer in the tsar’s army during the Great War. He considered himself to be part of the Russian middle-class and while also Jewish, he mixed well in liberal and elite Russian prewar society. Fluent also in German and French, he, along with my grandmother, was sympathetic to liberal reform movements. After the birth of my mother in 1917, Grunberg planned his first of three major escapes or moves – from their homeland, Russia. Liberal, cosmopolitan, and European, he wanted to ensure that his immediate family remained so, which is why he looked towards western Europe. It is unclear exactly when they left; by 1920 they had lived – en transit – briefly in Constantinople (today Istanbul) and elsewhere, where they acquired the so-called (stateless) Nansen, Passports. Living off the sale of family jewels they moved to Germany and settled briefly in Sonnenberg (now Slonsk, Poland), where he began a business exporting toys to the United States to his brother who helped sell them. In so doing he re-connected with his younger brother, Joseph Greenberg (aka Jacob Gruenberg), also known as Yossi, living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. And he began to send money to him should he in fact plan to come to Philadelphia at some point – so remembers his brother’s son, Leon, in memoirs that he wrote in his “Family Chronicles”.

Once in Berlin in 1922, the Grunbergs settled first in the Culmbachstrasse in the neighborhood of Schoeneberg, where many assimilated Jews also lived. Within a few years they settled in lovely apartment at a more fashionable address in Charlottenburg/Halensee: Paulsborner Strasse 79. During the 1920s the family also had spent some time in Prague in order to acquire Czech citizenship, which was an easier way to travel within Europe.

With Grunberg’s business partner, Isaak Trilling, he found the Dutch-German Trading Company (Niederlaendisches Deutsches Handelsgesellschaft), which was registered with the Berlin Chamber of Commerce; and sold a variety of goods, including toys, wheat, and fish nets in the United States and elsewhere. During this period, he also bought three apartment buildings (Insel Strasse 1A, Johannisstrasse 17, and Schwartzkopfstrasse 7); all three are in Mitte, the “downtown” of Berlin, as well as a property outside of the city: in Reiningsdorf Kreis Teldorf in Brandenburg. Two of three buildings were co-owned with Trilling; given their location and the fact that my grandfather contributed to the Jewish Community’s Kitchen Fund, he may have acquired them through the assistance or the guidance of the Community and rented them to other migrants, like himself.

While he clearly enjoyed his life in Berlin and helped create a comfortable existence for his wife, my grandmother, and his daughter, Ida, my mother, he worried about the rise of the Nazis. As an emigrant from a country in which he had experienced horrible pogroms (which may have contributed to the timing of his departure from Russa), he was quite aware of the dangers of fanatics, particularly those supported by their governments. Since he was apparently also planning to leave Berlin – as correspondence with his brother vaguely implies – it is indeed interesting that he bought the buildings in Berlin and not elsewhere. By 1931, as a man with foresight and without roots in Berlin, he did not believe that it would be wise to stay in Germany and yet he had numerous business affairs in Germany so that he would need to keep contact with his partner and his real estate manager, Helene Wagner (nee Troeger). As a European, in 1931 his/their next move was to Paris, where there had been a large Russian/Jewish exile community and where he and his family would feel comfortable and would provide excellent opportunities for all of them to rebuild his life and still return to Germany with his Czech passport as needed to fulfill his professional obligations.

The family’s fluency in French and having contact among other emigres made their move to Paris relatively uncomplicated. They settled in the 16th District: Boulogne s/ Seine 37 Boulevard d’Auteuil, a fashionable address and moved in a world of artists in Paris; during this period his business expanded into the production of motion pictures. While he had business in Berlin and returned, either by himself or with his family, at periodic intervals over the next few years to the city (as late as 1938), as well as used funds – rental income and/or loans — multiple times his properties until the summer 1939 to support himself and his family in their life in Paris, as well as interest from a bank account at the Commerzbank (Commercial Bank).

After the dreadful devastation after Kristallnacht [Night of the Long Knives] on November 9th, it was clear that the situation for him worsened and in December 1938 his three buildings were taken by the Nazis; in 1939 Mrs. Hedwig Kastens “bought” (illegally, of course so more exactly, perhaps expropriated!) one of them: Insel Strasse 1A. In 1939 Trilling also left Berlin; for Lodz, Poland, where he died – but the records are indeed confusing as to when he left – supposedly already in August or September 1938 (years later his sister Dora Saloweiczyk had moved to New York) and died there. In 1942 the Nazis also took the money from the Commercial Bank.

My grandfather’s health worsened and although funds were tighter; still they managed to live a luxurious life style in Paris. By the time Poland was invaded in 1939 the next step in the plan needed to be actualized – his health problems and the acquisition of a visa may have made deferred these plans. Still, he was Jewish and was quite aware that life could become precarious for them – should Paris be overtaken by the Nazis, as he now feared – so on the move again and planned to leave the Continent and head to the United States to join his brother’s family. During this period, he continued to transfer money to the States, since he was aware of the importance of showing that he would not be burden on the state and could support himself. In Paris contacts with the help of the United States Ambassador to France, William Bullitt, he began to make initial steps towards acquiring the needed visas. (see Appendix I, newspaper article in the Philadelphia Inquirer).

On June 4, 1940 they left Paris (where they now had lived for almost ten years) for the south of France in anticipation of acquiring visas to complete the last stage in their temporary sojourn: to go to the United States to join his younger brother, whom he had not seen in more than 30 years. An optimist he assumed that he could acquire visas – despite the complications of the system and given the bureaucracy and the quota system it was unclear whether their Czech passports would be accepted. Sadly, the details of this period are not completely clear. For almost a year (until May, 1941) they were in limbo – living in hotels (the longest was in the popular and centrally located Hotel Terminus in Marseille), waiting for clarification for visas, affidavits from doctors; the little information that I have been able to cobble together from a variety of sources. I am writing this post in part to see about getting more information to flesh out the details from others who may also have been in Marseille then and/or had relatives that may have been.

Leaving France was not uncomplicated. Apparently, their Czech passports didn’t help them to leave France. In February 1941 Hiram Bingham, IV, the Vice Consul in Marseilles, created affidavits for him, my grandmother, and my mother see for example A Rescuer in France: Hiram Bingham IV | Facing History and Ourselves The affidavit from my grandmother is still in my possession, along with the later information that indicates subsequent developments in her (and by extension that of my grandfather and my mother) travels through Spain and Portugal to the United States: See Appendix II.

With this documentation, as well as doctors’ affidavits, his brother’s sponsorship, as well as financial assets (that had been accumulating for more than 10 years that Grunberg had been sending to his brother in Philadelphia!) to support himself helped seal the arrangements. Interestingly, during this period they continued to live well, despite the war, and waited and waited. Memories are confusing; as to how harsh the situation is, as well as to how many times they had to relocate until they finally left France in May 1941 and appears that they sailed from Lisbon in June 15, 1941 on the Exeter and arrived in New York on June 24th: see Appendix III.

How did they do it? Yes, they had done all the “correct” things … and yet from whom did they help to leave at the last minute? From Fry? Bingham was by this time no longer in Marseille (he was sent to Portugal in April 1941). Perhaps Grunberg’s work in the motion picture industry, as well as his personal connection to some of the famous emigres, including Marc Chagall, may have helped him. The material appears to indicate that Chagall and his wife Bella were on the same ship to the States. It would be interesting to know if that were definitely the case.

Once in Philadelphia, they resettled there – interestingly they did not register with the City (at 2733 North 45th Street) until April 27, 1942. Ready to face new challenges, my grandfather was now finally safe from worry, and yet as a European he still had planned to until he could return to Paris (or even Berlin, where my grandmother had felt comfortable) when the war was over. His death in October 26, 1943 precluded those return plans.

While many facts of this story are missing, it is a fascinating story of perseverance in the face of different adversities, as well as the ability to embrace changes with zest, gumption, and even humor …. I am now writing this in the hope of gathering more stories about less well-known people, as well as learning more of the details of this period. One hopes that such stories will become a greater part of the literature of survival; after all, starting over is part of the title of my blog.

Appendix I: Philadelphia Inquirer Article, 10/26/1943

Appendix II: Affidavit in Lieu of Passport for Cheiwet Grunberg